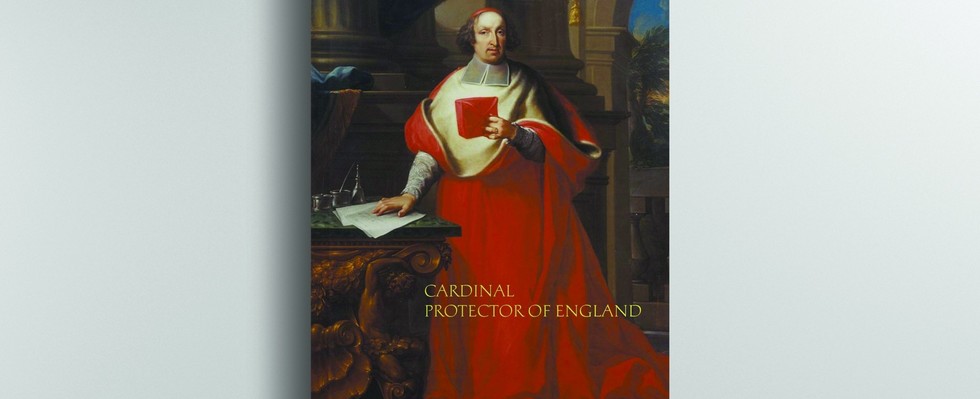

Philip Howard, Cardinal Protector of England by Godfrey Anstruther, OP (edited by Gerard Skinner)

Review by Fr Nicholas Schofield

Fr Godfrey Anstruther OP will be a familiar name to aficionados of English Catholic history, having produced a number of magisterial studies which are still used by scholars, including the four-volume biographical dictionary of the secular clergy between 1558 and 1850, The Seminary Priests (1968-77). Now, over three decades after his death, a new title can be added to his impressive bibliography: a biography of the seventeenth century Dominican cardinal, Philip Howard, for which he unaccountably failed to find a publisher in his lifetime. For some years following his death, the manuscript was feared lost but it has subsequently been found, and we can be grateful to Fr Gerard Skinner for editing it and bringing it to publication.

Chapels and calendars

Philip Howard is today a largely forgotten figure. He was the great-grandson of the martyr, St Philip Howard, and a grandson of the ‘Collector Earl’ of Arundel. As a young man, despite much family opposition, he entered the Dominicans in Rome and founded a small priory at Bornem, in what is now Belgium. After Charles II’s marriage to the Catholic Catherine of Braganza in 1662, Howard returned to London to serve as the queen’s Grand Almoner.

There are fascinating descriptions of Catholic life in the capital, where some of the splendour of continental Catholicism could be found at Court and the foreign embassies. These chapels were not always in tune with each other: the embassies, in line with much of Europe, followed the Gregorian calendar, while the queen’s chapel followed the English calendar, which had refused to accept Pope Gregory XIII’s reforms of 1582, removing ten days to catch up with the solar cycle. Thus, ‘a man might have gone to Mass at St James in 1664 and found the chapel draped in purple for Palm Sunday while his wife was listening to the organ pealing forth the joys of Easter in the chapel of the French ambassador’ (p.63).

Forgetting their English

Indeed, the book is full of intriguing vignettes and extracts from original documents. How many know that Dunkirk was occupied by the English between 1658 and 1662, and that it was suggested that an English bishop could be appointed there: he could be a ‘real diocesan’ on English territory, exercising jurisdiction over Catholics across the Channel but without trespassing on any existing English See (p.35)? Or that the custom of students at the Venerable English College in Rome speaking in Latin (except at recreation) was abolished for fear they were ‘beginning to forget their mother tongue’ (p.189)? Or that one of the sons of the poet John Dryden became a Dominican friar (p.275)?

Clergy squabbles

Anstruther notes that Howard lived as ‘the afterglow of the Elizabethan age had faded.’ For Catholics, the era of Campion and Persons had passed and, despite the bravery of many, ‘there is scarcely a name that is generally known, and nobody who showed outstanding gifts of leadership when a leader was desperately needed’ (pp.1-2). Many of the details of this book reveal the less edifying aspects of ecclesiastical history. Alongside the heroic martyrs and confessors are the squabbles among the clergy, the constant jockeying for positions at Court, the demands for a English Catholic bishop and the search of the Chapter (founded by the first Vicar Apostolic of England in 1623) for formal recognition. We hear of Howard’s bete noire, the Benedictine Edward Sheldon, and the rivalry between Archbishop Talbot of Dublin and the sainted Archbishop Plunkett of Armagh. Yes, then and now, the Church is both human and divine.

Foundations

Despite such tensions and the failure of many of his projects, Howard has long been worthy of a new biography. He not only helped lay the foundations for the English Dominican Province but was highly influential as Protector of England and the only English-born Cardinal between Reginald Pole and Thomas Weld (even though he never became an English diocesan). He was a prime mover behind the appointment of John Leyburn as Vicar Apostolic of England on the accession of James II in 1685. Three years later the country was divided into four Districts, a system of government which continued until the mid-nineteenth century.

Anstruther writes in a highly accessible way and has produced a biography that is made doubly impressive by the fact that Howard spent the last six months of his life burning his personal papers. Philip Howard is a timely and important contribution to our understanding of seventeenth century English Catholicism and its influence on the politics of the time.

Fr Nicholas Schofield is Parish Priest of Uxbridge and Westminster Diocesan Archivist.