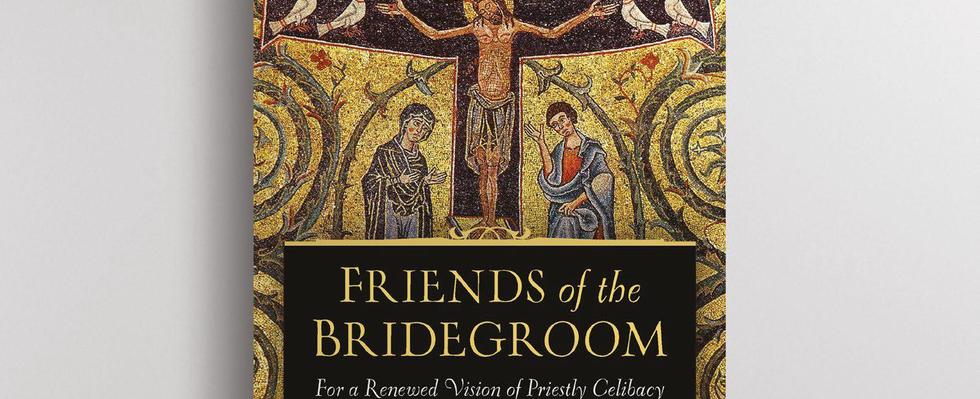

Book Review: A Visionary & Practical Theology of Celibacy

Reviewed by Fr. William Massie

Marc Ouellet was ordained priest during the summer of 1968.There was turmoil within the Church over the implementation of Vatican II, and Humanae Vitae was about to be published followed by years of enduring dissent with manifold consequences. In 1967 Pope Paul VI had just written an encyclical in defence of priestly celibacy which might seem surprising just two years after the Vatican II’s Decree on the Life and Ministry of Priests had just defended it. But even during the Council, voices, even episcopal ones, had called for the ordination of older, married men.

Fr Ouellet was a witness to this, and later as a diocesan bishop and now as Prefect for the Congregation of Bishops in Rome he has had a ringside seat in the appalling exposure of child abuse by clergy. This background informs Cardinal Ouellet’s observations and profound reflections in Friends of the Bridegroom. He has a broad, pastoral perspective, and as a former teacher of systematic theology at a Sulpician theological faculty (the Sulpicians specialise in the formation of priests) he has a deep knowledge of the re-framing of Catholic dogmatic theology after the Council.

Crisis of Identity

Friends of the Bridegroom is a collection of conference addresses and homilies given between 2012 and 2019. The focus is on priesthood. Rather than curse the darkness, Ouellet wants to light a candle, dispel the crisis of identity which he identifies as caused by a crisis of “faith and love” (p.174). There are a number of themes which he considers to be of vital importance if the Kingdom is to be proclaimed and the Church built up by attracting the right kind of men to the priesthood. His theological perspective is straight from the pages of the Vatican II Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium: almighty God wants to become visible and active |in the lives of men and women: we are to be caught up into the very divine life. How? Through the Trinitarian mission of the Church, the Sacrament of Salvation which effects what it signifies. Ouellet admits concern that this may well seem “theological and abstract” (p.234). But he is ever concerned to explain what he means in a way that is pastoral and attractive and above all shows forth the face of Jesus our divine saviour made man.

At the Service of the Faithful

So, what is a priest? Ouellet, seeking to move beyond a concept of the priesthood “too long limited to the service of ordained ministers” (p.239), begins with the one priesthood of Christ. Vatican II famously declared that the priesthood of the faithful and the ordained priesthood participate in this one priesthood but that the two participations differ “in essence and not just degree”. The language was loose and admitted of a variety of interpretations. Ouellet seeks a tighter explanation. He states that the royal priesthood of the faithful is a participation in the filial identity of Christ as beloved Son of the Father, echoing Augustine’s word that herein lies our dignity as baptised persons. The ordained priesthood is a participation in the headship of Christ as the visible icon of the Father. This hits the spot in explaining why the ordained priesthood must therefore be seen as at the service of the royal priesthood of the faithful and not a cultic caste ‘set apart’, hereby avoiding authoritarianism and clericalism. This also grounds the traditional maleness of the ordained priesthood. After the Council, in a commentary on the Decree on the Life and Ministry of Priests, Friedrich Wulf SJ speculated whether talk of “fatherhood in Christ” would have any appeal to younger priests. It seems incredible now but only because of the lasting impact of the pontificates of St John Paul II and Benedict XVI who helped to recover the essentials of our tradition and make them intelligible, credible and attractive.

Christ as the Bridegroom

What of a “renewed vision of priestly celibacy”? In fact, it flows perfectly (and logically) from Ouellet’s focus on the priest as sharing in the headship of Christ, to see whom is to see the Father. Ouellet recovers from the scriptures and our tradition the (theologically neglected) identity of Jesus Christ as The Bridegroom. Hailed by John the Baptist, fulfilling the prophecies of the Old Testament, this Bridegroom loves his Bride so much that he lays down his life for her, on the Cross. And this love-gift is made available for the Bride through all time in the Holy Eucharist, a pledge of future glory.

The ordained priest is the one who is given the power by Christ in the Sacraments of Order to make that love-gift available. How singularly appropriate that he be invited, called by Christ, through the Church, to lay down his life, like Christ, in love for the Bride by lifelong celibacy. Convincing

Ouellet enthusiastically quotes from the important Pastoral Exhortation of St John Paul II, Pastores dabo vobis (quoted indeed in practically every formal address in this book) the beautiful line, which builds on the courageous defence of celibacy by St Paul VI, “The Church, as Spouse of Jesus Christ, wants to be loved by the priest in the total and exclusive way in which Jesus Christ Head and Spouse loved her. Priestly celibacy, then, is a gift in and with Christ to his Church, and it expresses the service rendered by the priest to the Church in and with the Lord.” (PDV 29). In fact, so convincing is Cardinal Ouellet in his explanation and defence of the profound significance of the meaning and value of the celibacy of Catholic priests that it seems to undermine his deference for the tradition in the Eastern Catholic Churches of the ordination of married men as something “good and desirable” within our worldwide Church for particular reasons. In the 1980s, the founder of the Faith Movement, Fr Edward Holloway, wrote a short pamphlet on the priesthood with the title The Priest and his Loving. The idea of the priest as one who does not marry in order to love in a more completely Christ-like way, is very attractive. Ouellet believes (as did Holloway) that it will attract vocations and must guide priestly formation in the seminary.

Lives in Common

Most of the addresses are to clergy which is not surprising given the roles occupied by Cardinal Ouellet. He is visionary in a way that is attractive and practical. For example, as celibate priesthood is Christ-like and Christ’s life is profoundly Trinitarian, that is it is a life-in-communion, so too the lives of priests and bishops should be lived in communion, with their brother priests and bishops, in “face-to-face encounter” with their people and turned towards the world. Ouellet is excited by the prophetic, charismatic and energetic example of priestly life and mission of tenderness of Pope Francis.

Sin and Clericalism

Is anything missing? Cardinal Ouellet does not underestimate the grave damage inflicted upon the Church by the sexual abuse of the young by clergy. Perhaps it is understandable why a book seeking to provide a new vision of priestly celibacy would not wish to focus on what has gone wrong. But someone of the standing of Cardinal Ouellet needs to do that somewhere. Of course, it comes down to sin and sin affects the royal priesthood as well as the ordained. But it is the very clericalism condemned by Pope Francis and Cardinal Ouellet in the last pages of this book which so far seems not to want to go beyond expressions of profound sorrow and regret and provide explanations. A final point: it was John the Baptist who described Christ as the Bridegroom, “the one who has the Bride” (John 3:29), He described himself as “the friend of the Bridegroom” (ibid). Surely then, priests are not so much ‘Friends of the Bridegroom’ but ‘Other-Bridegrooms’ themselves – although this does not fall off the tongue quite so easily.

Fr William Massie studied dogmatic theology at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. He is Catholic University Chaplain in Hull and Vocations Director for the Diocese of Middlesbrough.