A Farewell to Holyrood Palace

POLITICS

John Deighan FAITH MAGAZINE July - August 2015

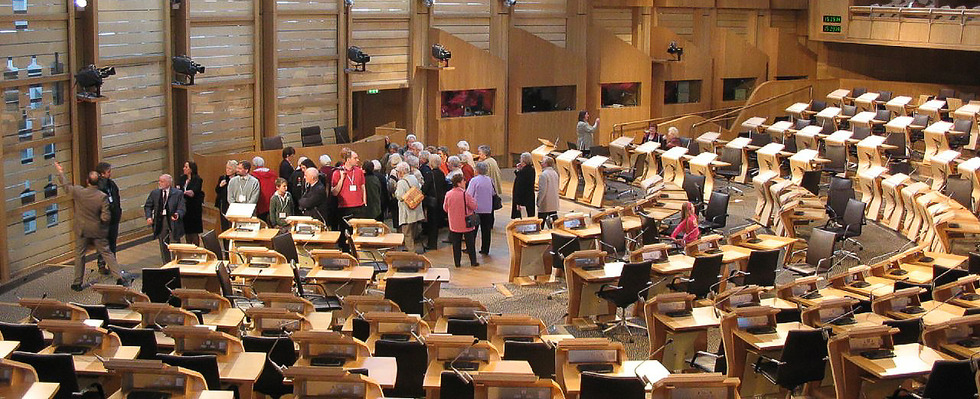

John Deighan has been the parliamentary officer for the Bishop’s Conference of Scotland since the creation of the new Scottish Parliament in 1999. This month he began work as chief executive officer for the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children Scotland. Faith magazine asked him to reflect upon his 16 years working at the heart of Holyrood.

In the middle of 1999 I expected that I would spend much of my time promoting the distinctive areas of the Church’s teaching. Little did I realise that it would so much centre on the understanding of the family and sexuality, and particularly on the legal treatment of homosexuality. It seemed just chance that, in assessing what the new political institutions of Scotland would be focusing on, I stumbled upon one research paper that would give me an immediate insight into what lay ahead. This was a paper based on research conducted in 1998 and published as a Scottish Executive Crime and Criminal Justice Paper (Research Findings No 41) and entitled “The Experience of Violence and Harassment of Gay Men in the City of Edinburgh”. What immediately struck me was the absurdity of the terminology and proposals in the paper – terms such as “heteronormativity” and “heterosexism”, which I’d never encountered before. But most startling was the scale of the ambition of the writers, which included proposing the benefits of “the removal of all legal distinctions between homosexuality and heterosexuality”.

Some research of my own on the issue quickly revealed a well-prepared social and political agenda for bringing those proposals to fruition. The effectiveness of that work is now evident. Not only has it been achieved remarkably quickly, but it has led in the space of a few short years to a situation in which those who hold to the previous understanding of family and sexual relationships risk losing their jobs and reputation should they happen to fall foul of the militant LGBT lobby.

The success of the social revolutionaries is an excellent study in how to bring about social change, albeit in this case change that has destabilised the very future of our society. What has been interesting is that our political classes are, by and large, indifferent to the importance of family life for the well-being of society. They have shown unthinkable negligence in failing to weigh up objectively arguments that might challenge the new orthodoxy – one which, seemingly overnight, has been imposed on our society.

The abandonment of the family is occurring largely for the sake of an exaggerated individual freedom which cannot, in the eyes of our social elites, be constrained even by gender identity or family structure. That mood has been absorbed even by people of faith who can think it judgemental to promote a truth if others claim it is offensive. But thus we rob future generations of the wisdom of our faith and cumulative wisdom gained over centuries of experience. It is easy to understand why Pope Benedict commented that he feared the collapse of reason more than the collapse of faith.

Another feature of the past 16 years has been the promotion of euthanasia and assisted suicide. Our generation’s absolute terror of suffering and the idolisation of personal autonomy make propaganda for killing the sick superficially appealing to the “worried well”. However, these issues start with the disadvantage (for their proponents) of trying to overcome the bulwark of human rights laws which, since the end of the Second World War, have increasingly placed duties on nations to protect life and to outlaw any deliberate deprivation of life. The issue of abortion is, of course, the exception, based as it is on denying the personhood of the unborn. Proponents of assisted suicide or euthanasia have worked effectively to create the social culture for their future success. But it appears most likely that the attempt to introduce assisted suicide in Scotland will fail yet again in the Scottish Parliament.

Another feature of political change has been the increasing faith in politics as the solution, even in the face of political failure. It is a measure of how effectively Marxism introduced the idea of messianism into politics – the idea that somehow, despite the evidence, a political strategy and new laws will deliver a wonderful society for us all. No one believes this more than our generation of politicians, and in their efforts to bring about such a society they have taken to intervening ever more readily in our lives – all too often, unfortunately, with the approval of the majority of citizens. The warnings of Alexis de Tocqueville’s study of democracy in America should be made widely available for those who are concerned about our political future.

The Scottish Government is not alone among advanced European democracies in legislating or creating new initiatives at every turn when some social problem arises. Eating, smoking, drinking, depression, teenage pregnancies, infertility, fitness, parenting … all now need some government minister or official to tell us how to live. That every child in Scotland has a government-appointed guardian shows how far we have come. Thanks to the breaking of social bonds in our families and communities, and the lack of self-control that a culture of indulgence promotes, we will continue to become more bureaucratic and inefficient in our governance, while at the same time creating the conditions whereby citizens become less capable of leading their own lives.

I realise that the situation can seem bleak. But despite appearances I am hopeful that we are on the brink of positive change. A new generation has grown in the midst of secularism and they have somehow remained loyal to the Catholic faith and the natural reason that it endorses. There is an opportunity to build from such a basis and to turn away from the dreadful darkness of our culture (spiritually and humanly) which is killing innocent children in the womb.

My new role will give me the opportunity to work with others in building a culture of life and to implement some of the lessons I’ve learned from others who have effected social change. Our success in defeating assisted suicide shows that mobilising good people and promoting the truth can be effective. I hope to do much of that in the future.

John Deighan is the chief executive officer for the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children Scotland.